Our most insightful urban commentators generally agree that the liveliest cities are those with greatest diversity. Diversity of activities, diversity of people. Jane Jacobs long ago highlighted the link between economic diversity and social vitality; how the former fuels the latter, how economic activity ensures the presence of people, concentrations of people, different kinds of people, who in assorted ways all help keep economic activity afloat.

Henri Lefebvre, in France, made pretty much the same point, if in a different register. He wasn’t so much interested in the economic forces that create diversity as how diversity creates dynamic encounters. Cities, for him, are sites of encounters, dense and differential social spaces in which people assemble. City spaces come alive through proximity, through concentrations of different social groups and activities, gathering in place. Lefebvre said the enemy of encounters—indeed the enemy of urbanisation itself—is segregation and separation, two profoundly anti-urban impulses.

Over past decades, the diversity that Jacobs extols and the encounters animating Lefebvre’s urban visions have had their work cut out. The form and function of our cities have been moving in the exact opposite direction. Jacobs emphasised the need for high- and middling-yield enterprises mingling with low- and no-yield enterprises. Instead, predatory city economies have throttled small businesses: high-yield has become the only asking price. Many corner stores as well as corner people have been forced out of business and out of town. Cities have become functionally and financially standardised, predictable and unaffordable, predictably unaffordable, sucking dry their vitality, their Jacobean life-blood.

Over past decades, the diversity that Jacobs extols and the encounters animating Lefebvre’s urban visions have had their work cut out. The form and function of our cities have been moving in the exact opposite direction. Jacobs emphasised the need for high- and middling-yield enterprises mingling with low- and no-yield enterprises. Instead, predatory city economies have throttled small businesses: high-yield has become the only asking price. Many corner stores as well as corner people have been forced out of business and out of town. Cities have become functionally and financially standardised, predictable and unaffordable, predictably unaffordable, sucking dry their vitality, their Jacobean life-blood.

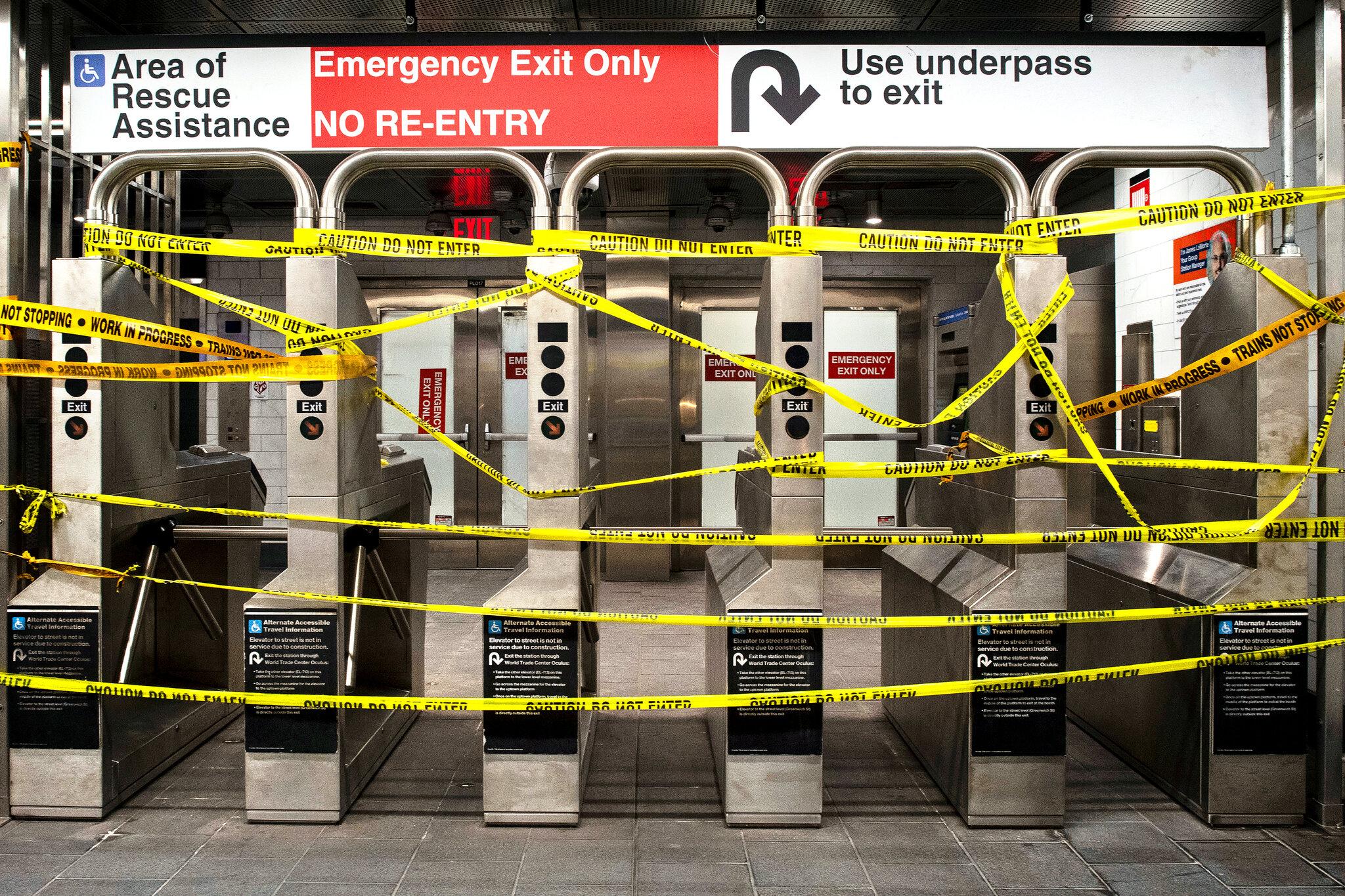

Meanwhile, COVID-19 has assailed world, upending urban life as we once knew it, intensifying those existing pathologies. Economic distancing had been gnawing away at the urban fabric for awhile, executing the separation Lefebvre feared so much. Now, social distancing explicitly breaks into urban densities, crimping cities as sites of physical encounters. Suddenly, our new urban reality is one of de-encounter, a thinning down rather than thickening up, the dispersion and dilution of city life, its fear and avoidance.

As the pandemic raged, the rich who’d hitherto been colonising citadels everywhere, shaping them in their own crass class image, exited fast. Same story the world over: a wealthy urban exodus, a hunkering down by the shore, up a hilltop, at the country estate, anywhere without people. Between March 1 and May 1, the first two months of lockdown, 420,000 of New York’s wealthiest quit town. Manhattan’s Upper East Side emptied out by 40%. Denizens fled to second homes upstate, in Long Island, in Connecticut and Florida. “Farewell Poor People,” said the Daily Mail (March 19, 2020), catching the spirit of London’s select out-migration. Its most well-heeled populations similarly headed for rural sanctuary, paying up to £50,000 per month in rentals. British estate agents have since been inundated with requests for country mansions and isolated manor houses.

In times of plague, the rich outrunning the spread of infection has been a time-served tactic. Daniel Defoe, in A Journal of the Plague Year (1722), describes the harrowing scenes of the 1665 “Poors Plague,” the bubonic epidemic that struck London, striking it unevenly. The famed author of Robinson Crusoe narrates his tale of the Great Plague through the lens of an alter-ego character, an independent merchant, H.F., who’d agonised about whether to stay or flee London like his class peers. Eventually, unlike them, he decides to stay put, even ventures out, and walks the streets and bears witness to the mass slaughter of a terrifying disease few understood.

In 1665, Defoe would have been a five year old lad, so A Journal of the Plague Year is a novelistic invention—an artistic creation based on historical fact. Like the good journalist he was, Defoe did his research thoroughly, read meticulously around the plague, the books, pamphlets and scientific studies, and H.F. evokes graphic details reliably accurate and believable from the standpoint of an authentic observer: the desolate streets and parishes, the shut-up shops, the over-run cemeteries, the fevers and vomiting, the pains and swellings, the destruction of whole families and the reality of 97,000 Londoners perishing because of a bacillus now known to be a parasite of rodents, transported by fleas.

H.F. is a sympathetic, if eccentric, flâneur, both fascinated and frightened by the disease, compassionate about the calamities afflicting populations that bore its brunt, that suffered the greatest body count. Even the poor’s insurrectional tendencies found an understanding ear. At one point, he distinguishes between “good” and “bad” mobs, between dissenting peoples whose marauding cause seemed legitimate, and those who seemed to be acting because they’re deluded by false propaganda. This sounds oddly contemporary, a refraction of our own COVID-19 crisis moment, with growing economic inequities ripping apart society, cross-cut by ideological battles between mask wearers and right-wing anti-maskers, Black Lives Matter protesters and white supremacists. Separation and segregation here encounter one another. Our public life has fractured into trench civil warfare, even more dire than in Defoe’s seventeenth-century.

Public space is a menace, a threat to public health, not only because of the spread of virus, but also because it is fraught with violence: “I can’t breathe,” is one expression, immortalising George Floyd’s dying words on a Minneapolis street, as a white cop pressed his knee into the black man’s neck. “Don’t shoot!” is another, after Michael Brown’s valedictory plea in Ferguson, Missouri, just as the police opened fire, heralding a spate of police killings of young, unarmed black men (and women). Such homicidal tendencies beget a few questions: What remains of the public realm? Is it for population-level wellbeing, for public safety? Or is it for individual liberty, for the right of a person to freely express themselves?

Right-wing libertarians say forcing people to wear face masks in public is an assault on individual freedom, an infringement of personal liberty. It’s a perverse logic, another instance that unfettered self-interest is best; that a greedy drive for profit maximisation and unregulated consumer choice brings about a healthier, more robust society. It doesn’t. It’s a big lie, a foil for a selfishness that bears no responsibility for how it hurts others, economically or otherwise. The mask isn’t only a personal protective equipment: it’s there to ensure other people’s health isn’t put at risk. There have to be limits to what is deemed acceptable individual behaviour in public. There’s more need than ever for a social contract, for a democratic covenant in which everybody recognises duties as well as rights, accepts that our inner selves are constructed through a social identity.

It’s a touchy subject. Yet it’s an agenda Jean-Jacques Rousseau set himself over two and half centuries ago, forty years after Defoe’s Journal, and its basis remains instructive about what we still lack: “a form of association that defends and protects the person and goods of each with the common force of all.” “I had seen that everything is rooted in politics,” Rousseau said, “and that, whatever the circumstances, a people will never be other than the nature of its government makes it.” “Great questions as to which is the best possible form of government,” he thought, “seems to me to come down in the end to this one: what is the nature of the government most likely to produce the most virtuous, the most enlightened, the wisest, and in short, taking this word in its widest sense, the best people?”

These days, people are far from virtuous, enlightened and wise. As presidents and prime ministers bully, lie and peddle misinformation, stoke up hatred and division within society, they’ve rendered us stupid. They’ve destroyed our ability to judge truth from falsehood, good sense from (social) media nonsense. Some describe this as a denigration of our “cognitive immunity,” the destruction of our mental defence system, the ability to ward off pathological ideas, just as our immune system might ward of a pathological disease. (Elsewhere, I’ve called it a “mystified consciousness,” following Lefebvre’s thesis from the 1930s.1) What we have is what we deserve, an anti-social contract, a model of government that has hoodwinked its populace into believing it is free, that it is upholding its individual liberty, when in actuality we are enslaved.

Past pandemics—from plague in Ancient Greece and the Roman Empire’s Plague of Justinian, to Europe’s bubonic epidemics in the Middle-Ages and eighteenth-century, passing through typhoid and cholera outbreaks in the nineteenth, onwards to “Spanish flu” in 1918 and the latest COVID-19 epidemic—have all revealed underlying crises in their respective societies. Plagues sparked terrible tragedy, yet were often outcomes of crises, not initial causes, a symptom of something lurking within the culture, about to give, a growing malaise, soon to worsen. COVID-19 is not so different, exposing structural defects in our economy and politics, our encroachment into the natural world, our destruction of it, and how zoonotic diseases like COVID-19 now more virulently jump from animals to humans. When COVID-19 struck, our mix of under-funded public and for-profit private healthcare systems proved woefully inadequate to cope. The virus spread like the wildfire and flash-flooding evermore frequent in our midst. Another hurricane had hit, and our urban system, which had long been in an endgame crisis, took a pounding.

Endgame happens when a space-hungry rich displace the poor from the city’s checkerboard, when they banish all but a few pawns from their isotropic plane of business immanence. As buildings go up in cities, partition walls move in for millions of people. Speculative space opens up, dwelling space closes down, gets sliced up and subdivided to maximise rents and property values. Wealth for the few resonates as crampedness for the many, little squares for the pawns. The lack of affordable housing in every big city across the globe has pushed more and more people into tiny (and expensive) shoebox lives, and studies show how micro-dwelling negatively affects our health and happiness—even in “normal” times.2

History is maybe on our side, expressive of long-wave good news. Over the centuries, humans have survived tragedy through the incredible stoicism of not moving, of standing one’s ground, of resisting, of engaging in tremendous creativity. Wars, plagues and mass ransackings of cities in Ancient Greece gave us poetry like The Iliad, epic drama like Trojan Women, scholarship like Thucydides’s History of the Peloponnesian War and Plato’s Republic. When bubonic plague hit seventeenth-century Britain, theatres closed and Shakespeare’s plays could no longer be performed. But none of this prevented the bard from writing them, from letting his creative juices flow, in the misery and isolation, penning such masterpieces as King Lear, Macbeth and Antony and Cleopatra.

In the mid-1850s, Marx lived through a cholera epidemic in London’s Soho, killing hundreds of people because of a contaminated water pump. Marx was destitute, had several children die before him, lodged in a truly dreadful, cramped apartment—this as economic crisis deepened and workers’ revolt dissipated. Nonetheless, he continued to work, never stopped studying capitalism, never let up writing Das Kaptial. He never stopped hoping, either, telling his comrade Friedrich Engels that “in all the terrible agonies I have experienced these days, the thought of you and your friendship has always sustained me, and the hope that, together, we may still do something sensible in the world.”

In the twentieth-century, disgust with an economic and political order that plunged us into two murderous world wars helped spark Surrealism, a revolutionary movement that affirmed its own extraordinarily creative dialectic. On the one hand came Max Ernst’s brilliant pictorial horror story, “After the Rain II,” painted between 1940-2, a hellscape of hope smothered by petrified and calcified structures, by corpses and decayed vegetation, by deformed creatures in a prehistoric premonition of our own COVID-19 fate.

On the other hand emerged an optimism, an art and literature that celebrated the dawn of romantic love, the primal form of the Surrealist encounter, epitomised by André Breton’s Mad Love. Fascist bombs rained on Guernica and Hitler’s Third Reich was about to stomp across Europe, yet Breton wrote: “I have never ceased to believe that, among all the states through which humans can pass, love is the greatest supplier of solutions, being at the same time in itself the ideal place for the joining and fusion of these solutions.” (Three decades on, John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme nodded in agreement. As racial hatred raged across America, its triumphant choruses sought “resolution” through love, as well as the “pursuance” of this love resolution.)

Perhaps what we’re experiencing now is an interregnum that progressives need to ride out, need to struggle through, sustain ourselves by hope, by a love supreme, by friendship, believing there’s light somewhere beyond the darkness, some way still to do something sensible in the world. This too will pass. Hopefully. Perhaps we can use the time alone, in quarantine, to think collectively, to reflect together on how we might reconstruct the public realm of our cities, even the public realm of our lives. Maybe we need to start by thinking up a transitional “public sphere,” incorporating the virtual into the real, developing online links with others, collapsing the social distance on the outside through time-space compression on the inside, via our computer screens, through the Zoom communities that continue to sprout.

In our private households, we can plot another public world, do it together, from the underground, as it were, where dissidents and activists have traditionally hidden out when the political going has been rough. There we might reframe the notion of “intimacy,” tweak its meaning in the interim. With Zoom, after all, not only can we look into people’s faces: we can also enter into their homes, into their personal spaces, see the art on their walls, the books on their bookshelves, the family photos, share a strange sociability and camaraderie that helps us almost touch one another. It’s not ideal, not the same as face-to-face encountering; but let’s use it nonetheless, let’s try and find partial nourishment in this interregnum, by sharing ideas, launching discussion and reading groups, webinars and virtual gatherings, talk and debate and listen to one another, organise one another, forge solidarity in kind, if not in person. It’s a first-cut attempt at scheming a new beginning.

There have been hints of what post-pandemic cities might do to bounce back. Usually this involves smaller-scale design rather than any vaster public planning. The key issue seems to be ushering in fresh air into urban life, creating cities that flourish in the open, in the public realm, making them al fresco playhouses, bringing a touch of Ancient Greece back into our civilisation, when open-air amphitheatres became scenes of mass political and intellectual communion. Researchers indicate that we’re twenty-times more likely to catch COVID-19 indoors than outdoors. So there’s need to reimagine a different open-air public life, more resilient to future pandemic, with different spaces and places, accessible spaces and places, with commercial and recreational activities that not only entice people back into cities, but offer enough to make us want to stay, to feel safe as well as stimulated.

Design initiatives propose squeezing roads to widen pedestrian sidewalks, enlarging café and restaurant terraces; radiant heating and cooling technology can extend outdoor seasonal usages. Future cities will be a lot greener, more walkable and bikeable. Cars and car-oriented infrastructure will get scaled back. Abandoned lots and obsolete multi-storey car parks might flourish as urban farms, using hydroponics, providing cheaper, fresher produce for neighbourhoods, on their doorsteps, minimising food miles and distribution costs. Such innovations now seem de rigueur, standard repertoires in design game-plans. Ditto opening up streets and parkland to vendors and commercial activity, reanimating open-air city retailing, allowing it to be improvised and spontaneous—maybe like it once was.

After decades of “quality of life” campaigns, this would be an enormous volte-face for a city like New York. Since the mid-1990s, during Giuliani’s mayoral years, Business Improvement Districts have waged war on unlicensed street activities, converting Manhattan into a glorified corporate suburban theme park, funnelling people into the chain malls and cleansing the streets of grubby diversity—of food stands and street peddlers, of artists and homeless booksellers, stuff that brought vitality to many sidewalks.

Al fresco city life has always thrilled our most romantic urbanists. Their ideal visions invariably affirmed the outdoors, the street. They sat in cafés, wrote books, fretted home alone; but their real muse was without a roof, amid the crowd, out on the sidewalk—no matter the weather. It was an open-air intimacy, amongst strangers. Poet Baudelaire suggested we embrace the crowd, bathe in the multitude, take universal communion, find ourselves as we get lost in public, merging with the masses, though not too close. Surrealist André Breton recognised his great heroine, Nadja, enjoyed being nowhere but in the street, “the only region of valid experience for her, in the street.” Nadja, the phantom woman who’d chosen for herself the name “Nadja,” because in Russian it marked the beginning of the word hope, and because she, Nadja, was only a beginning.

Lefebvre’s urban encounters were likewise street-based and streetwise. For him, streets were modes of attraction and assembly, of union and proximity, of human co-presence. Jane Jacobs said the liveliest streets have the most dynamic choreographies—“intricate street ballets,” she called them—changing with the time of day, never repeating themselves from place to place. We’ve seen some of these choreographies adapt and change over past months, as dancers dodge and sway, twirl with other members of the ensemble, guarding social distance on city streets everywhere. But Jacobs knew that sidewalks needed more than just urban design to keep them alive, more than a street bench here, a charming park there. Design alone, she suggests, can only go so far. We need a bolder vision of how to reintroduce public life. How might we recapture the diversity and vitality dear to Jacobs’s heart? Especially since her cherished small businesses and street corner societies have been heading towards extinction.

Local commerce needs life-support even more than it did pre-COVID. 21,000 British small businesses went under during March’s lockdown. The British Chamber of Commerce fears as many as one million little enterprises might collapse soon, leaving empty shells and boarded up main streets across the land. New York lost 3,000 small businesses during its March quarantine. Many Manhattan street corners, even in neighbourhoods like Greenwich Village, are boarded up and graffiti-splattered. Big retail chains have made conscious choices to elope. After years of plundering Manhattan, seeing off little independent competitors, sucking life out of many New York blocks, big brands like Gap, J.C.Penney, Subway, Domino’s Pizza lead the charge out.

We need a public action plan that restricts private interests chomping away at the common wealth. In our largest cities, this common wealth has been squandered by conspicuously wasteful large enterprises, administered by elites who thrive off unproductive activities: they roll the dice on the stock market, dance to shareholder delight, profit from unequal exchanges, guzzle at the public trough, filch rents and treat land and property as a pure financial asset, as another money-making racket. Invariably, too, they dodge their fair share of the tax burden. They leech blood money out of urban territories and underwrite what might be termed “parasitic city” development, antithetical to the “generative city” that any public action plan would now need to reinstigate.

Accumulated wealth ought to be reallocated to benefit ordinary people and public infrastructure. Top of this plan’s agenda is making city life viable for little businesses as well as little people. There’s need here to impose some kind of commercial rent and business rate control. When urban economies thrive, commercial landlords jack up rents, speculate and inflate property markets, become the “monstrous power” that Marx recognised. “One section of society,” Marx said, “demands a tribute from the other for the right to inhabit the earth.” In downturns, when the economy dips, landlords prefer to sit on vacant property, leave their premises empty until they find tenants able to pay the market rent, the inflated market rent. It’s a double whammy that inevitably works both ways against less resourceful tenants.

A carrot option for municipalities is to offer landlords tax incentives to release commercial space at more affordable rents, making it worth their while to see rents reduced. Yet there are harder alternatives, too, bolder policies that might be pursued, which necessitate a stick. One could be the creation of a “living rent” program, a landed counterpart to the living wage ordinances already passed in many cities around the world. A living rent would be a rent that enables small business owners to earn a living, to pay for a lease in accordance with their modest income streams. In a property market designed not to screw everybody, potential small business concepts might actually become real practical endeavours; little entrepreneurs are encouraged to take the risk, to go for it. A living rent would allow landlords to receive a rent-controlled return, a fair return, not an extortionate, parasitic return, subject to taxation at an appropriate rate. Leases would be negotiated over five-year terms. At each renewal, living rents would be recalibrated according to the tenant’s past and prospective future earnings. Refusal of landlords to comply to living rent ordinances would mean that the municipality sequesters the property, procures it as a public landlord.

Imagine, in such an incubating culture, what little generative activities might flourish. By themselves, they’d be modest ventures. But scattered around a whole city, they’d collectively add up to a lot. They’d signal the return of the re-skilled worker in the city, empowered in their labour-process, answerable to themselves as well as their locale. These artisans would pioneer little start-ups the likes of which we’d already begun to glimpse, pre-COVID. In grungy, abandoned areas of town, we’ve seen micro-breweries and distilleries prosper in small-scale fabrication units. Let’s hope they continue to prosper, and have others emerge alongside, post-COVID: bakers and candlestick makers, bookbinders and printers, potters and carpenters, furniture repairers and cheese-makers, welders and sculptors, clothes and craft producers, artists and urban farmers. We can imagine them together, bringing a little diversity and curiosity back into the ’hood, adding vitality to an everyday ordinariness of grocery stores and corner delis, who’ll now equally be able to make the living rent.

Meantime, city officials need think hard about what they’re going to do with the glut of office space remote home-work now betokens, the new norm for the privileged white-collar employee. Much of this office space was speculatively built, produced by over-accumulated capital, colossally unnecessary even at the best of times. Now, at the worst of times, we have it, looming large, a dark cloud hanging over urban space, threatened with devaluation. It’s a lesson in how to kill a city, to make large swaths bland, the kind of blandness only money can buy. But here, again, imagine how vast open-planned floors could be rezoned and converted into affordable individual dwellings and family homes, with real space between partition walls, fitted out with balconies and breathable outdoor terraces. City governments could obtain the leases or the freeholds of these premises, recruit local architectural practices to engage in innovative designs; local construction companies might undertake the actual rehab itself.

Importantly, some of this affordable housing would need to be set aside for younger people. Since lockdown, millennials have undertaken a mass urban exodus, too, and this flight out continues everywhere, from New York and London, to Paris and Tokyo. Even before COVID-19, younger people were wilting under the pressure of exorbitant big city costs, enduring tiny domestic spaces because of the wealth of amenities outside, on their doorstep—the bars and restaurants, the theatres and art galleries, the cultural attractions, the sheer energy of flocks of people, the sense of opportunity. Yet given that many of these attractions remain closed today, and that streets are shorn of people, costly big cities have quickly lost their lustre. Their bright lights have dimmed. Many millennials have left, some opting for cheaper small towns, others working remotely from their parent’s home, wondering if they’ll ever return to city life again.

It says a lot about our civilisation, about what’s gone wrong: young people fleeing cities because they’re too expensive, because the high cost is no longer worth the hassle, that the city’s promise has been a let down. It equally bodes badly for our urban future, when so much young creative capacity decides to up sticks, leaving a worrying urban footprint in its wake. Historically, cities were places where young people always flocked to, went there to liberate themselves, to grow up in public, as independent adults, beyond the grasp of their parents. The city was an existential rite of passage. Now, as the cost of living soared, the city’s romance was already talking alimony.

Anybody who has ever watched French nouvelle vague cinema, directed by the likes of Jean-Luc Godard, François Truffaut and Louis Malle, will have felt this urban romance, imbibed its moody atmosphere. Much of the dialogue and action in these films unfolded in the street, in the everyday public realm, on a café terrace, up and down the boulevard, day and night. The city was a site where young people fell in and out of love, argued about politics, read books, discovered themselves, extended themselves. In cities you broadened your horizons, deepened your whole being. Few young people went motivated by money. Indeed, cities were places where the young preferred to be poor, because there you led a richly adventurous life.

The city itself was portrayed here as a sort of Great Book, as a seat of higher learning, as an open-air library where one learned, received a humanist education about how to be a public person, with civic rights and responsibilities. There, almost unwittingly, you engaged in what the American educational philosopher Robert Hutchins once called “The Great Conversation.” How to initiate a Great Urban Conversation nowadays? How to get people talking again about the city in humanist terms? Not just map it on a moneyman’s spreadsheet, or run it through a technocrat’s algorithm. The Great Urban Conversation is to dialogue around our collective destiny. Might we find the civic leadership courageous enough, visionary and intelligent enough, to step up to the plate, to accept this challenge, to help us discover a new urban social contract together, to make our minds as well as our cities generative again? It’s hard to tell. Some days it seems impossible. Yet despite the apparent hopelessness, I can’t quite give up the ghost, can’t quite give up hope for a time beyond the coronavirus, beyond what we have now, beyond Trump, beyond Johnson—for a time when our urbanism might inspire rather than plague us.

Notes

- ↩See Andy Merrifield, “Mystified Consciousness,” Monthly Review 71, no. 10, pp. 14-21 (March 2020).

- ↩See Andy Merrifield, “Endgame Marxism (and Urbanism),” Monthly Review 71, no. 6, pp. 47-53 (November 2019).