As president-elect Andrés Manuel López Obrador prepares for his inauguration this coming December in Mexico, he is a step away from inheriting a country witnessing its worst human rights crisis in a century. Since 2006, the numbers of killings and disappearances attributed to the drug war and organized crime have surpassed 150,000, and 2018 is well on track to being the most violent year on record in Mexican history. López Obrador, or AMLO, recently released a light-on-the-details four-point plan outlining how he proposes to address deep-seated problems of corruption and impunity in the judiciary and law enforcement. AMLO could show he is serious about taking a new approach to tackling these problems by bringing justice to the families of those who were disappeared during Mexico’s dirty wars in the 1970s.

Neither the violence nor the impunity of officials in today’s Mexico is unprecedented. On October 2, 1968, 50 years ago today, police and military forces gunned down hundreds of students in downtown Mexico City, just days before the opening ceremonies of the Olympics. This massacre marked the beginning of a brutal dirty war between the government and guerrilla groups that spanned both cities and the countryside. In 2002, then-president Vicente Fox released many of the military and secret police files pertaining to the 1968 massacre and ensuing dirty war. En lieu of a Truth Commission, Fox set up a special prosecutor’s office to look into whether or not charges were necessary. While victims met this news with much hope, they soon grew disillusioned. No one was ever brought to justice for the atrocities government agents committed in the name of national security, and the public has been given only the vaguest outlines of what took place, who was responsible, and how many suffered. The special prosecutor’s office was eventually disbanded and, since 2015, the majority of the files Fox released were informally reclassified. Both in the past and today, despite concerted attempts by victims and their families to hold the perpetrators of the abuses accountable for their crimes, little has happened. This lack of accountability is on display this month as civil society groups and victims across Mexico mark the 50th anniversary of the 1968 massacre.

It is within AMLO’s power to change how the justice system tackles its long track record of tolerating, ignoring, and abetting human rights abuses from the past and the present. Government security forces detained, interrogated, tortured, imprisoned, and in some cases disappeared these family members. They did so in the name of national security, to punish their relatives and act as a cautionary symbol to dissuade others from joining one of the many armed guerrilla groups that sprung up in the aftermath of the 1968 student massacre.

One group of victims—the relatives of the so-called subversives from the 1970s guerrilla wars—offer clear parameters of what could be done today in cases of innocent victims. Today, the families are asking for official recognition of what was done to them and reparations for their pain and suffering. These victims have waited for almost five decades for some form of legal reckoning for what was done to them and AMLO could help them find the answers and justice they have sought for so long.

Take, for example, the family of Lucio Cabañas, the former school teacher trained at the Ayotzinapa rural teachers college, who became the leader of a guerrilla group known as the Party of the Poor from Atoyac, in the state of Guerrero. It is no coincidence that this is the same region where 43 students were disappeared on September 26, 2014. Cabañas’ relatives collectively suffered the wrath of the military and police forces that swept through the area in the counter-insurgency campaigns of the 1970s. The family faced harassment, endured countless threats, were repeatedly robbed, and forced off their land. Several were taken to detention centers at the military base in Pie de la Cuesta or clandestine prisons in Acapulco and Mexico City. Some, such as Lucio’s cousin, Isaías Castro Velásquez, were detained and never returned. Those left behind sold off their belongings and gave up their jobs to search for their disappeared loved ones. This harassment continued even after the guerrilla leader was killed in a shootout in 1974.

The scale of what this one family endured became evident as we interviewed a dozen survivors over the course of these past few months. The military detained Pablo Cabañas, Lucio’s younger brother, in January 1972 and, as he told me, “my life changed completely.” As the soldiers questioned him about Lucio’s whereabouts, Pablo explained to us that they “slapped [us] across the face, hit [us] with a club, kicked, electric shocks all over the body, inside the underpants, almost naked, stuck us in a barrel of cold water, submerged our heads, hands and feet tied up, thrown on the floor to be kicked wherever we fell.” Pablo spent almost six years in prison and was finally released in 1977. He has brought lawsuits against the government about his unlawful imprisonment and testified before various official bodies, including the Attorney General, to no avail.

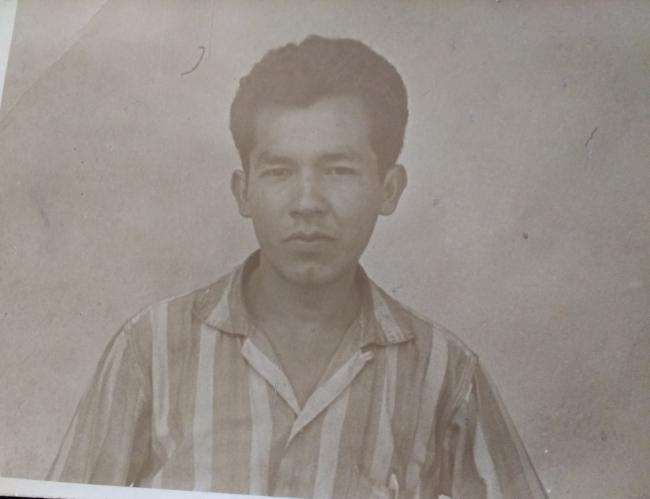

Adolfo Godoy Cabañas, Lucio’s cousin, tells a similar story. He was detained, interrogated, and imprisoned for four months in 1971. In our conversation, he explained how his family had suffered irreparable damage. He pulled out a photograph of himself standing outside his cell at a military base in Mexico City. “This photo is proof of my disappearance.”

“We were disappeared but our family refused to stop looking for us,” explains Bartola Serafín Gervacio, Lucio’s half-sister. She spent two years detained inside clandestine prisons inside military bases in Guerrero and Mexico City along with her mother, sister, brother, husband, and two small children. Bartola explains how her husband and brother were tortured, and how she, the other women, and the children were put in solitary confinement for months on end. Though only six at the time, Bartola’s daughter, Mariela, recalls her fear, nightmares, and hearing the screams of fellow prisoners being tortured.

The family endured even more pain beyond that—a sampling of what so many others faced in this brutal era. Two members of the Cabañas family, including Lucio, died during combat between the guerrilla group and security forces; five others—four men and one woman—were detained and subsequently disappeared. Eighteen of them, including men, women, and children of varying ages, were detained, tortured, and imprisoned for anywhere between hours to six years. At least one woman from this last group, María del Rosario Cabañas Alvarado, subsequently died from injuries she sustained during torture. There are others like the Cabañas family, whose members must be accounted for as victims.

As Mexico gears up to mark the 50th anniversary of the massacre of students in 1968, AMLO could stand apart from history by promising that the judiciary will finally answer the Cabañas family, giving them the reckoning they so deserve. AMLO has shown he appreciates the value of symbols in politics. This is the man, after all, who opted for a 60% pay cut in his salary as president and spent hours sitting on a commercial plane on the tarmac of Mexico City’s airport to showcase his refusal to use the presidential plane. Bringing justice to the Cabañas family on this anniversary would make a powerful statement, even more so because it comes on the heels of the four-year anniversary of the disappearance of the 43 students from Ayotzinapa.

Making this announcement to the Cabañas family on such an occasion will elicit hope that impunity is no longer sacrosanct in Mexico and the government is serious about tackling this issue both in the past and the present. It would also go much further than President Enrique Peña Nieto’s recent announcement that the 1968 student massacre was indeed a “state crime.” There were other state crimes beyond what happened at Tlatelolco that Mexico must reckon with. Beyond acknowledging the horrors of Tlatelolco, AMLO should recognize what happened to the families targeted by the counterinsurgency campaigns of the 1970s, in the repression of popular uprisings in Chiapas and Guerrero in the 1990s, and against many of the innocent civilians caught up in the current drug war. Bringing closure to the Cabañas family’s search for reckoning would thus be an important first step for AMLO to take as he embarks on a long journey to address entrenched impunity that thrives in silence and in relegating to oblivion the pain of so many across five decades.

Gladys McCormick is associate professor of history and the Jay and Debe Moskowitz Chair in Mexico-U.S. Relations at the Maxwell School of Citizenship and Public Affairs of Syracuse University. Her research interests include the political and economic history of Latin America and the Caribbean, corruption, drug trafficking, and political violence. She is the author of The Logic of Compromise: Authoritarianism, Betrayal, and Revolution in Rural Mexico, 1935-1965 (2016, University of North Carolina Press). She is currently working on a book exploring the history of torture in Mexico since 1970.