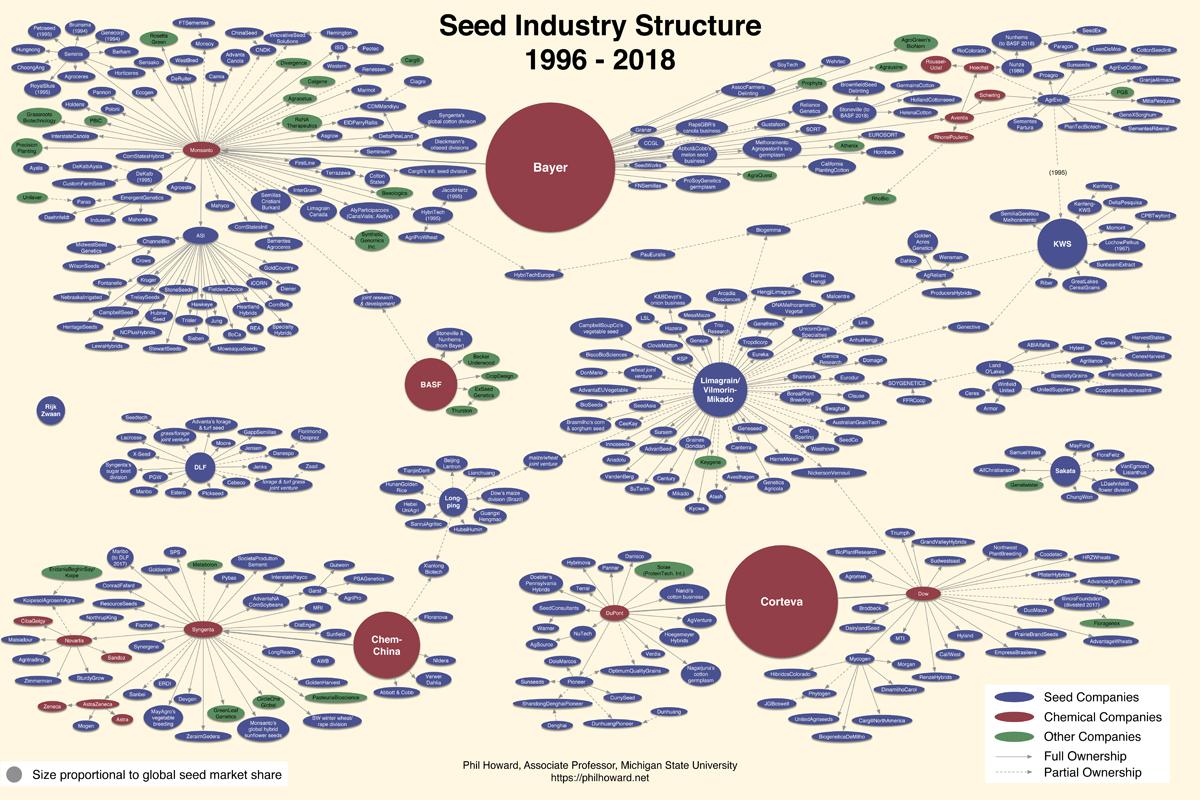

When Philip Howard of Michigan State University published the first iteration of his now well-known seed industry consolidation chart in 2008, it starkly illustrated the extent of acquisitions and mergers of the previous decade: Six corporations dominated the majority of the brand-name seed market, and they were starting to enter into new alliances with competitors that threatened to further weaken competition.

Howard’s newly updated seed chart is similar but even starker. It shows how weak antitrust law enforcement and oversight by the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) has allowed a handful of firms to amass enormous market, economic, and political power over our global seed supply. The newest findings show that the Big 6 (Monsanto, DuPont, Syngenta, Dow, Bayer, and BASF) have consolidated into a Big 4 dominated by Bayer and Corteva (a new firm created as a result of the Dow–DuPont merger), and rounded out with ChemChina and BASF. These four firms control more than 60 percent of global proprietary seed sales.

Howard began his annual tracking of seed industry ownership changes in 1998, a year that served as a turning point for industry consolidation. Two years after genetically engineered (GE) varieties were introduced in 1996, by 1998 the large agribusiness companies had accelerated their consolidation by buying up smaller firms to accumulate more intellectual property (IP) rights. By 2008, Monsanto’s patented genetics alone were planted on 80 percent of U.S. corn acres, 86 percent of cotton acres, and 92 percent of soybean acres. Today, these percentages are even higher.

Economists say that an industry has lost its competitive character when the concentration ratio of the top four firms is 40 percent or higher. The seed industry continues to exceed this benchmark not only across the entire global supply, but across crop types as well. For example, even before the Big 4 merged, three firms (Monsanto, Syngenta, and Vilmorin) controlled 60 percent of the global vegetable seed market.

The most notable mega-mergers in Howard’s updated chart include:

- • Dow and DuPont: This $130 billion merger resulted in the two chemical companies dividing into three companies, including a new agriculture firm called Corteva.

- • ChemChina and Syngenta: This $43 billion merger allowed China to add its second company ranking in the top 10 of global seed sales (along with Longping High-Tech).

- • Bayer and Monsanto: This $63 billion deal was the second-biggest merger announced in 2016; Bayer has since dropped Monsanto’s 117-year-old name.

“For farmers, the options continue to be reduced,” says Howard. “Although Bayer sold a number of seed divisions to BASF to pave the way for its acquisition of Monsanto, the share of the market controlled by the largest firms has only increased.” What’s more, he added that although those firms made promises of job growth and greater innovation if the merger was approved, Bayer last month announced it would cut 12,000 jobs, or about 10 percent of its global workforce.

History shows us that seed industry consolidation leads to less choice and higher prices for farmers. These companies also aggressively protect their IP rights, which means less innovation and more restrictions on how seed is used and exchanged, including for seed saving and research purposes. These restrictions affect conventional and organic agriculture alike by making a large pool of plant genetics inaccessible to public researchers, farmers, and independent breeders, which in turn limits the diversity of seed in our landscapes and marketplace and weakens our food security.

A number of studies suggest increased market domination removes companies’ incentive to innovate. The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s own data confirms this trend, finding that fewer players mean less innovation. As the seed industry became more concentrated, private research “dropped or slowed” and those companies that survived consolidation are “sponsoring less research relative to the size of their individual markets than when more companies were involved.”

While the three mergers mentioned above received the most media attention and public resistance, Howard’s latest report found that 2018 brought 56 additional acquisitions and joint ventures involving other top seed companies, including Limagrain’s Vilmorin-Mikado subsidiary in France and Longping High-Tech in China, which acquired Dow’s maize division in Brazil. Both ChemChina and Longping High-Tech are planning more acquisitions of seed companies in China.

“There is a strong need to make these hidden ownership ties more visible to both farmers and eaters,” Howard explains, “so that we can avoid supporting firms that threaten the resilience of our food systems.”

Seed represents profound potential for improving our food and agricultural systems. Plants can be bred to thrive without pesticides and to naturally resist disease, and to be adaptable to changing climates and environmental conditions; they can also be bred to improve the quality of our food. But to realize all of this potential, we must create structural changes to how seed is managed and shared.

The DOJ has abdicated its responsibility to investigate and prosecute violations of antitrust laws, meaning that it is up to the public to demand action and resist companies that put the sustainability and security of our food and farming future at risk. We must also demand and support more investment in public plant breeding programs that are truly responsive to the needs of regional and resilient farming systems that support the health of both people and the planet.

As the industry continues to consolidate at a scale previously thought unimaginable, and policymakers begin to grapple with solutions, there is a growing community of seed stewards who are making an immediate difference today. Seed leaders including Ellen Bartholomew, Edmund Frost, Walter Goldstein, Ken Greene, Sarah Kleeger and Andrew Still, Frank Morton, Judy Owsowitz, Laura Parker, Theresa and Dan Podoll, Clifton Slade, Don Tipping, Rowen White, and many others are actively increasing the security of our seed and food supply.

By supporting more democratic seed systems—whether it’s buying from a seed company that aligns with your values, visiting your local seed library exchange, or growing and saving your own seed—we can take back control of our seed supply while actively conserving, improving, and generating more diversity on farms and in our backyards. This is the kind of diversity that, when considered collectively, is globally important.